Introduction: In a lab, as in many places, several humans need to rely on shared resources.

One example of this resource is the storage space on the shared computer needed for data acquisition. This resource is key to allow the acquisition of further data, the spearhead of any scientific process.

Problematic: When this resource is occupied fully, further acquisition becomes impossible, hence blocking the major input in science at its very source. The solution is seemingly easy, people should free this resource as it is no longer needed on the acquisition computer, and displace it to the data analysis computers.

Method: A junior Grad student sends an e-mail to the lab members, asking to remove unnecessary data.

A model is proposed to explain the data removal dyanmic in fontion of time, as it would be in a theoretical world.

Empirical data are collected at the scanner at different time interval to monitor the response of the lab members to the signal "Please remove data"

Model:

The change in data space is modeled in function of time, and is thought to be, the sum of the action of every lab member, which is a direct response to the signal, an e-mail. E-mails are read at different intervals between lab members, which can be set to a constant for every colleague i. Each lab member thus informed is models to response directly after the signal, put work aside for the minute it takes to connect remotely to the computer and to remove his/her unused data.

This model does not take into account the vacancies in the the lab/office, which, in a science lab, can be negligible. The reaction time of a colleague i, is thought to be minimal and was not included in the model.

Since on average every lab member, reads his/her e-mail once a day, all data should be removed over a 24h period, 48 h in a catastrophe scenario.

Results:

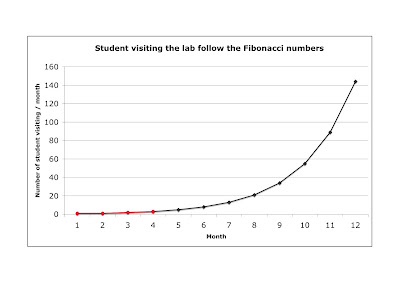

Figure 1 shows the response over time of the data removal process which took place after the announcement of a a crowded hard drive on the data acquisition computer. It is worth taking note that the first 2% data removed was removed by the junior grad student. Overall 4.5% of the data where freed. This is a strong deviation from the theoretical model. Furthermore, past a 24h delay, the e-mail elicited no response from the lab member

Discussion:Strong deviation for the theoretical model where observed in the empirical investigation.

The possible explanation come from the fact that the data removal signal was emitted from a junior student, it is possible that more senior member, who also have the most data sitting on the data acquisition computer, have simply ignored such a message from a junior lab member.

It might be interesting to compare the reaction time when the signal emanates from a post doctoral fellow, a senior scientist or the lab leader.

Further more, it might be that the data occupancy is forgotten by its owner, had will continue to remain on the hard drive for as long as the owner is not reminded of his property.

Conclusion:

The model proposed was a fairly too optimistic was to characterize the data removing process. Other factors need to be taken into account to model the data removal response.